This week, the United Nations reminded us of some of its old glorious days when the General Assembly, almost unanimously, voted to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The old lady in New York was an important world stage that day, where a rarely convincing decision was made against one of the founders and a permanent member of the Security Council. The United Nations has not had the political power to influence the course of important world events for a long time, but the vote against Russia still had a strong world echo, especially its convincing outcome of 141 to five.

Like the entire order of international law, the UN is a refuge for the voice of the small and an opportunity to be equal with big, sometimes with such important decisions, and sometimes with at least small gestures that draw world attention. Khrushchev pounded his shoe on his delegate-desk, Castro spoke for four hours instead of 15 minutes, Bolivian Evo Morales brought coca leaves, which he also grew, to the podium, and Hugo Chavez made the sign of cross behind the podium after a speech by George W. Bush, saying that before him the devil was there and the smell of sulfur is still in the air.

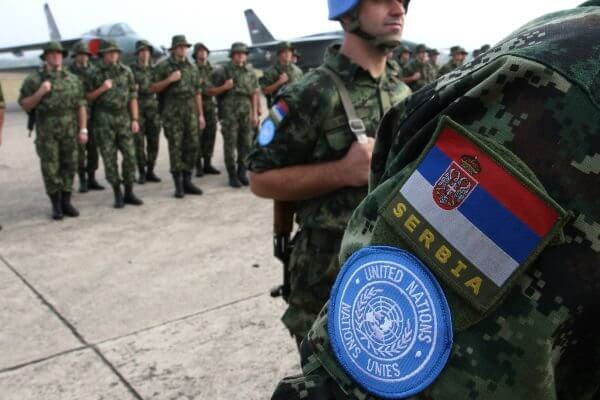

Serbia was one of 141 UN members that condemned Russia for invading Ukraine. It had every reason for it, maybe more than the others. Not only because it is a violation of all international charters, but also because it was a victim of identical legal violence. And most importantly, it voted in accordance with its state interests, and that is the only motive and reason why everyone comes to New York for UN meetings, even the eccentrics who have been making circus on those meetings for the past 75 years.

Everyone in the European Union applauded Serbia’s vote, this move was welcomed by the United States and all neighbors in the region, and Croatian Television especially registered it in a report from New York. It’s like it was a big surprise, but is it true? It seems that they expected that Serbia would vote against its interests, in order to protect Russia’s interests for some reason. And Serbia came to the East River, in fact, with the same job as Russia – to say what its interests are and to defend them. They didn’t coincide, but that’s nothing new or surprising either. In the past few decades, there has been an abundance of such discrepancies, and that is exclusively due to the will of Russia.

Let’s start with the United Nations. Russia has never imposed sanctions on us, and this is often heard, and it is simply not true. Out of about 150 resolutions passed by the Security Council in the early 1990s regarding the disintegration of Yugoslavia, a dozen provided for penalties and sanctions against the then FR Yugoslavia, that is, Serbia. Starting with the ban on arms exports on September 25, 1991 (Security Council Resolution 713), until May 30, 1992 (Security Council Resolution 757), when sanctions and unprecedented blockades were imposed on us, after which we were expelled from the United Nations. There was no Russian veto on these decisions.

Russia continued this attitude towards Serbia even before the bombing. Resolution 1244 did not fall from the sky, before that four were passed over the conflict in Kosovo, where Serbia was being warned about violating peace (Security Council resolutions 1160, 1199, 1203 and 1239), an embargo was imposed on arms imports (UN Security Council Resolution 1160 of March 30, 1998), and the Hague Tribunal was asked to collect information on crimes in Kosovo (Security Council Resolution 1199 of September 23, 1998), all with the support of Russia, because it was in its interest.

Outside the UN, but in connection with them, Russian leaders have reminded countless times that their interest can be in direct conflict with the interests of Serbia. Putin and his friends justified the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine by wanting “Srebrenica not to happen again” in Donbass. They have been saying so since 2008, when Lavrov justified the attack on Georgia by saying that “Russia could not allow acts of genocide, as was the case in 1995 in the Bosnian city of Srebrenica”. Yes, Lavrov then used the word “genocide” for the Srebrenica crime for the Wall Street Journal. Because it was in Russia’s interest.

Many times since then, Moscow has used Srebrenica to justify its policy towards Donbass. Putin connected these two things for the first time in 2017 in Sochi, and repeated those words two years later, as he did now when he launched the invasion of Ukraine. In the meantime, his lower associates, such as spokesman Dmitry Peskov or Dmitry Kozak, Deputy Kremlin Chief of Staff waved with the Srebrenica massacre in the context of Donbass. Clearly, it is in their national interest.

Russian battalion’s spectacular arrival from Bosnia to Kosovo in June 1999 turned out to be only in Russia’s interest, but not in Serbia’s, when it was withdrawn as soon as they heard that they had to bear the costs of their mission in Kosovo and that their supplies were blocked. Russian soldiers, celebrated by Serbs as some liberators, left Kosovo completely by August 2003, which Putin justified by saying that with Russia’s military presence he did not want to cover up “Kosovo’s development in the wrong direction”. And withdrawal is, therefore, good if it is in the state interest, Russia’s state interest this time as well.

The declaration of Kosovo’s independence has opened the door for Russia to play a double game, to challenge it in principle as a violation of international law, and at the same time to use it for its offensive plans against its neighbors. Maria Zakharova, for example, said that the Kosovo precedent opened the possibility for Abkhazia and South Ossetia to secede from Georgia, and after that Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk. Moscow recognized all of them as independent states, because that is its interest, regardless of the fact that it directly collides with Serbia’s interest in Kosovo. When Putin and Lavrov said in the first days of the invasion of Ukraine that only those states that represent the entire nation on their territory have the right to sovereignty, then that should mean that Serbia does not have sovereignty over Kosovo, because it is not accepted by Kosovo Albanians. Again – exclusively the interest of Russia, regardless of anyone else’s interest, and in this case, again at the expense of Serbia.

These days, the image with the coat of arms of Russia is spreading on social networks, over which is written – If Serbia imposes sanctions on Russia, then I am against Serbia! It is not the Russians who write that, but the people from Serbia. Those who are convinced that their native country must not have any interest, not even the right to have it, but that the interest of a foreign country is the only one and most important. Such an attitude towards one’s country has its name somewhere at the bottom of moral and human misdeeds, but it also has a criminal-legal definition.

In contrast, Serbia has acted in the UN as a mature and responsible state, whose president represents exclusively the interests of his country and the interests of his people, and for that he has the highest moral justification. Serbia also had before it a historical memory of the cold embrace of Russian “brotherly love” from the past few decades, some of which we have briefly recalled here. It is a reminder that states and nations have only and exclusively interests, not human emotions. Russia has been reminding us of that for decades, and it is time to understand it correctly, in the interest of Serbia.