Crises are not completely bad. They make people and entire societies wiser, because by their consequences they are forced to learn faster than they would have been if the situation were normal. Crises are gates that accelerate our social maturation as we go through them. In every such passing we get scratches, sometimes smaller and sometimes bigger, but we always come out better and more prepared than we used to be.

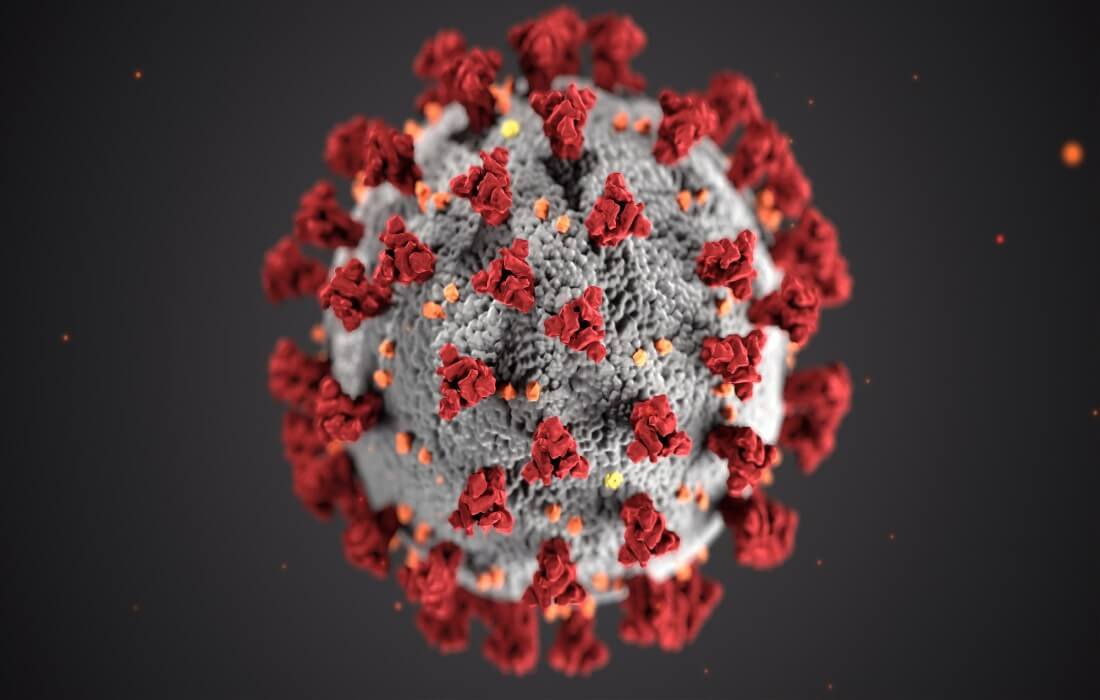

Prior to December 2019, the world had vast knowledge of infectious diseases, gaining it through historical experience, learning, and going through hundreds of epidemics that claimed millions of lives. Yet not enough knowledge for a new infection that has stopped the entire planet in two months, for the first time since its inception. That big and clever world became smaller than the smallest living thing, the invisible killer we knew something about, but not enough to counter it.

Fear of the unknown is a basic human feeling, difficult to overcome and resist. It can only be fought with knowledge, and it is never final. The little Corona reminded us of this brutally. Knowledge is undoubtedly what drives us through crises so that we get out of them with as little harm as possible, but we are also led by people who have the capacity to manage not only the known, but especially to deal with the unknown. These people are leaders. One of the leading people at Google and AOL spoke about them, saying that “managers manage the known and the leaders unknown”.

What does managing the unknown look like today, in the age of the Corona, when the stake is human lives?

China, in which the coronavirus has invaded the human species, has done much to keep the unknown unknown. Suppressed doctors’ efforts to inform the world of the threat, did so reflexively, protecting its authoritarian system from bad news infection. In doing so, it endangered the entire world, which received too late the alarm that lives were in danger. China’s silence was backed by a chaotic World Health Organization reaction that ignored the timely warning from Taiwan (because Taiwan, for Christ’s sake, is not a UN member) that the virus was transmitted from person to person, and on January 12 it declared that people were safe from the virus, which was then the official, but also incorrect, interpretation of Beijing. Mistakes were made, proportionally lacking in leaders’ ability to deal with the unknown. Frozen by the apocalyptic news from Italy, the European Union was disappearing under the rise of national ramparts to defend against infection. From one another, EU member states stole loads of masks, gloves and respirators, trampling on the dark airport warehouses the famous European solidarity, its fundamental value on which the EU emerged as the most successful peace project in human history.

Donald Trump made fun of the virus until it flooded, like a tsunami, the coast of his great land, and began killing thousands, turning New York into a concrete desert, full of field hospitals and collective cemeteries. Britain first decided to give in to the virus, to use herd immunity strategy and wait for the virus. Until projections from Oxford and Imperial College showed that the outcome would be catastrophic, so Boris Johnson government promptly build a dam, joining the rest of the barricaded world.

From the first moment, Serbia started sharply, closed almost hermetically to the outside, and no less loosely to the inside. “One of the most rigorous measures in all of Europe,” the Associated Press wrote about Serbia in mid-March on the occasion of the state of emergency. At that moment, it sounded like criticism, but Serbian imprisonment before the Corona was becoming European practice day by day. Those who missed days and weeks defending their freedom of movement or lifestyle, as the highest values, soon began to count hundreds, even thousands, of the dead.

If Serbia and its leader Vučić were at least somewhat left alone by the world media for “rigid measures,” they were nevertheless retained as a leitmotif for another story. Thanks to China, which was the first to send necessary medical supplies to Serbia (the one around which EU member states scrambled), Vučić became an example of China’s sudden “soft” influx on European soil, through so-called Corona diplomacy. Serbia and its president have become stars of innumerable “analysis” in the Western media, with one and the same conclusion – they are the best example of how China is trying to “wash its hands” from the responsibility for spreading the virus worldwide. China’s medical support to Serbia, however, is minor in comparison to the one that went to the heart of the EU, Italy and France above all, it is incomparably smaller than the one that arrived in New York from Russia. However, we should ignore such similar pamphlets, shaped by inertia that has long held Serbia as a Russian or Chinese “asset” in the middle of Europe. Because pandemic will change many things, including this one.

In the course of the virus crisis, Aleksandar Vučić has shown strong leadership qualities. He had a clear vision at the beginning (prevent casualties), had a clear strategy to implement that vision (measures to combat the epidemic, crisis staffs…) had knowledge (health experts), had money (saved over the past years through strengthening public finance). And most important to our story, he had allies on all sides of the world. That’s why his first aid came from China and then from the European Union, a little later from Russia and the US. The Guardian is one of the few who “does not cling” to the story of Serbia as a Chinese Trojan in the middle of Europe, but shrewdly concludes that Vučić’s Serbia has positioned itself as a bachelorette for whose hand the world’s greatest players compete.

The crisis has only completely illuminated what has been happening in Serbia and with Serbia for the last eight years. And there is an attempt to make one, and on a European scale, small country, to forge strong alliances with as many players from the pinnacle of global power as possible, without much concern for their conflicts. That’s their thing. The crisis has only shown where Serbia will move after the crisis, and most of the planet seems to be moving along that path. And this is a much greater opening up to each other, loosening of the conflicts so far (trade wars, sanctions, protectionism, blockade of international agreements…) and probably restoring the global order to a “factory setting”, embodied in strong multilateralism, influential international institutions and mutual cooperation. Of course, a crisis never ends with a return to the point that preceded the crisis. The crisis always leaves some of the temporary measures and relationships that were only valid for that period. You come out of the crisis changed, usually for the better. Those people and those societies that are capable of predicting the “unknown” are coming out of the crisis much stronger than they were. Winston Churchill assumed leadership at a time when Britain was frightened, when it had no vision, freed it from fear and led it to victory, because he had a clear picture of the future Britain and the future Europe, as well as the ability to persuade his followers in the feasibility of that vision. Serbia, like all other countries, will, after the pandemic, step into a new world. A world that will look for a new model for its functioning. It will be something unknown to many and will require a leader to manage that unknown. It looks like Serbia has already done the job.