The section of the road from Kosovo to Niš was, until recently, a nightmare for Albanians during vacations and large migrations of visiting workers. Along with the risky driving and winding road, there were occasionally actual issues brought on by locals waiting for them. For amusement, they either charged to escort their neighbours in a convoy of cars to the first toll booth or simply directed them to side rural roads away from the Niš highway that takes them to Western Europe.

Even though they had no idea why the “Shiptars” were their greatest enemies, they saw it as a small act of retaliation against them. They merely learned that they ought to treat them in that way. They were satisfied with petty scams, believing they were performing significant national service, so returning to their miserable lives without jobs and prospects in a region where the salary is far below the national average was a little bit simpler.

Since the funding for its construction first started to be raised a few years ago, and in particular, since the works began, there has been an ongoing discussion – Who needs this road? By its senselessness and particularly by its malice, the question takes us back to the end of the 19th century – Who needs a railway from Belgrade to Niš? It also raises a new question – How did some individuals manage to remain the same for 150 years, despite advancements greater than those made in all previous civilisational eras combined? Which cave did they reside in that allowed the greatest advancement in history to pass them by?

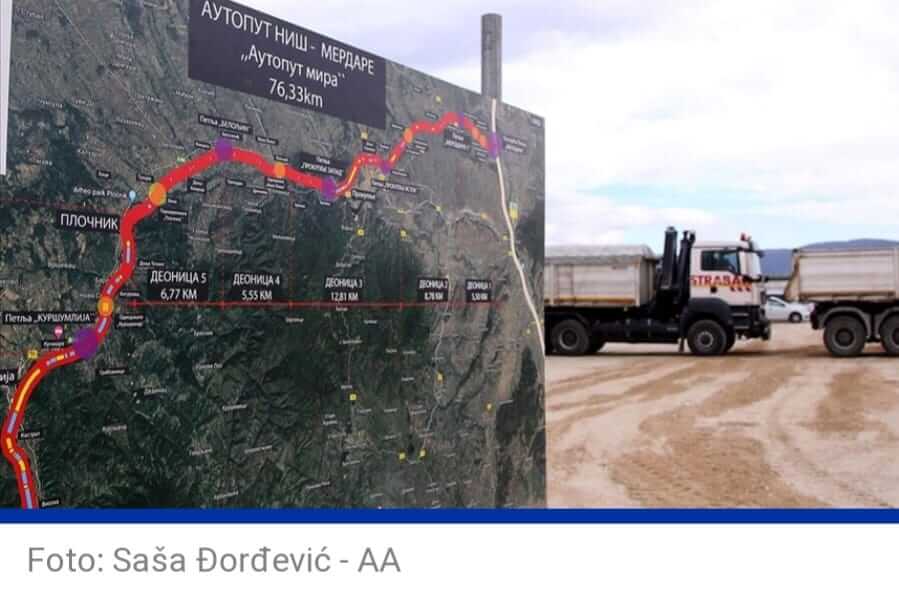

Aleksandar Vučić recently opened the first 5.5 kilometres leading to Kosovo and Albania. He repeatedly underlined the importance of this road for Serbia while appearing odd to the assembled Europeans, who are mainly responsible for funding this project.

They asked themselves – Why does this man have to explain again how significant the road to Merdare is? Isn’t that obvious? Clearly, it is not. There was always a curse waiting for him after the opening. People from the previous administration, which built exactly zero kilometres of the highway while in office, made fun of the phrase “only” 5.5 kilometres.

One of them, Dragan Đilas, even filed a lawsuit and staged a performance in front of the court, claiming that there is no highway, only half of it and said that someone stole the other half.

The others were less creative. They stuck to the old question/finding – Serbia does not need this road, but only the “Shiptars” – to travel faster, to reach Europe easier, and even to smuggle drugs easier (I guess that’s all they do and no other job)!? It will be the “backbone of Greater Albania”, said one opposition leader.

This was increasingly more beautiful music to the ears of those idle guys from the beginning who had been ambushing families with young children every summer and sending them to the mountains instead of the Niš highway.

One of the craziest criticisms of Vučić’s highway to Merdare says that only NATO needed this road, so it could more easily and quickly transfer its troops through Albanian ports to Eastern Europe, if necessary!? The hero who exposed this global conspiracy against the Serbs and thus stood side by side with flat earthers and anti-vaxxers is a respected interpreter of political events, a frequent guest of “serious” opposition media, who still take him seriously.

None of them had ever considered that every road had two directions, so even this one from Niš to Pristina does not possess the supernatural ability to allow traffic to flow in one direction only. The one deemed nationally unacceptable.

It has never occurred to anyone that the road would be practical primarily for people from Prokuplje, Blace, Kuršumlija and the surrounding areas. Not to mention that because of this new road, some new jobs will open up in this region, precisely because a good road, railroad, gas and Internet are the first things that investors ask about when they search for a place for their investment.

What makes this road unique compared to all other sizeable construction sites in Serbia, and why is there such a commotion and clamour surrounding it? How did it deserve that all those who work on it, particularly Vučić, be blamed for national treason even because of it? That little piece of about 70 kilometres is much more than an ordinary road. Its “culpability” is that it has been tearing into pieces the most deeply rooted misconceptions and prejudices, which have cost the whole of Serbia, particularly the south, decades of decay, misery, and even human lives.

With the construction of this road, Serbs and Albanians have the chance to reconcile and, at the very least, travel more swiftly and comfortably to one another’s locations, trade along the way, and get to know one another without fear of ambushes or retaliation. Whether they will use that chance depends on them, but there is no better start than a good road.

Niš-Merdare is a European-Serbian project, and that is its second biggest “problem”. The construction is funded by European residents—around 40 million euros have been donated so far—and by favourable loans from the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Serbian citizens have also contributed financially, since the state budget helped pay for some of the work. The whole business stemmed from the Berlin Process, a large European project to economically raise the Western Balkans and bring it closer to Europe.

It is difficult for Vučić’s opponents to accept all this because they are convinced that Europe is making a fatal mistake when it invests in Vučić’s Serbia, instead of isolating it, even at the cost of leaving a large part of the country without people, overgrown with forests and weeds.

For those on the right, it is hard to bear that by building a significant road, Vučić is finally promoting a region known for patriotism and war heroism instead of leaving it to them and their complaints about the heroic and insurgent Toplica being deserted.

On this short piece of road, the biggest frustrations of those Serbian politicians who did not correct a single wrong south of Niš during their rule, let alone bring and manage an investment of half a billion euros, intersect. From the other direction comes the despair of all those who wish that Serbs and Albanians would forever remain blood enemies, between whom there can only be a fighting trench, not a road that connects them. On the third side is Europe, which they are angry with for funding this road during Vučić.

Fortunately, the new road through Toplica, paid for with money from European and Serbian funds, unravels this tangle of hatred and delusions woven carefully and expensively over decades. It is important to note that all its opponents will drive it fast and easy today.